(Bloomberg) -- Treasury yields declined Friday after President Donald Trump threatened new tariffs, reigniting concerns about damage to the US economy and sparking a stock-market selloff.

The bond-market rally drove yields lower across maturities, led by the two-year, which fell as much as nine basis points to 3.90%, the lowest level since May 9. That was the last trading day before the US and China agreed to a trade truce that unleashed a surge in stocks and Treasury yields.

Short-dated yields priced in better odds that the Federal Reserve will cut interest rates twice by year-end to help the economy. Longer-maturity tenors declined less — and remain higher on the week — as tariffs also are expected to prove inflationary. Trump threatened a 50% tariff on the European Union as well as a 25% levy on some Apple Inc. products.

“We have another dose of uncertainty this morning,” Russell Brownback, a portfolio manager at BlackRock Inc., said on Bloomberg Television. “The curve has evolved into a stagflationary outcome.”

Stagflation — a combination of sub-par economic growth and elevated inflation — could curb the Fed’s willingness to lower interest rates, prolonging economic woes. JPMorgan Chase & Co. chief executive officer Jamie Dimon earlier this week said stagflation can’t be ruled out as the US grapples with huge risks from geopolitics, deficits and price pressures.

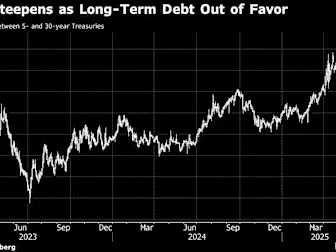

The US 30-year yield briefly declined as much as six basis points to 4.97% before rebounding to 5.04%. It exceeded the five-year note’s yield by a full percentage point this week, the widest gap in more than three years.

Demand for long-term Treasury debt has been sapped by perception that the US fiscal outlook is getting worse. The US House of Representatives this week passed a tax bill that’s been estimated to increase the federal deficit by $3.8 trillion, and Moody’s Ratings last week stripped the US of its highest credit rating.

The US 10-year term premium — or the extra return investors demand to own longer-term debt instead of a series of shorter ones — has climbed to near 1%, a level last seen in 2014. It’s a measure of how jittery investors are about plans to raise the scale of future borrowing.

“The sweet spot is to be in the front and the belly where you almost get that yield, similar to the long-end, without all the volatility,” Brownback said.