(Bloomberg) -- US President Donald Trump’s tariffs threaten to batter Japan’s vital auto industry and derail the country’s long-standing efforts to engineer a sustainable economic recovery.

With the 25% US tariff now in place on cars and auto parts, Japan’s major automakers — including Toyota Motor Corp., Honda Motor Co., Mazda Motor Corp. and Subaru Corp. — are bracing for a collective hit of more than $19 billion this fiscal year alone. And it’s not just the household names feeling the pain.

Northwest of Tokyo in Gunma Prefecture, where Subaru operates its main factory, the effects are already being felt. With costs rising, Yoshiyuki Nakajima, president of Shoda Seisakusho Co. — a supplier to Subaru — warned that his firm will be forced to slash profit margins if the tariffs persist. Worst case, layoffs will be unavoidable. “We’ll have no choice,” he said.

That sentiment is emblematic of the broader turmoil rippling across Japan’s industrial heartlands, where a dense web of small and mid-size suppliers form the backbone of the automotive sector — the country’s largest source of exports and a key provider of jobs and investment. Two-thirds of Japan’s workforce is employed by firms with fewer than 1,000 people, and many of those jobs are tied, directly and indirectly, to the auto industry.

The trade shock hits just as Japan is starting to see signs of a “virtuous cycle” — a loop of rising wages, stronger spending and higher prices that policymakers hope will lift the economy out of its decades-long stagnation. Now, with auto companies reconsidering wage hikes and pulling back on growth plans, the momentum that Japan has worked hard to build is at risk of stalling. Around 64% of polled economists see the tariffs sparking a recession in the world’s fourth-largest economy.

Even before the levies, companies like Shoda Seisakusho were struggling to keep up with the global shift to electric vehicles. Nakajima has had to cut staff at two factories in China and freeze new investments. He now sees pay increases for his 200 workers next year as challenging. With the US tariffs added to the mix, the outlook is grim.

“I often say that there’s no bright future for us if we simply continue running our business in the same way,” Nakajima said.

The Japanese government is scrambling to contain the fallout. Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba, who’s preparing for a national election next month, needs to show he can defend Japan’s economic interests. His chief trade negotiator Ryosei Akazawa is expected to travel to North America for the sixth time to try and win concessions ahead of the G-7 summit in Canada on June 15, where Ishiba may meet with Trump face-to-face.

Analysts see Tokyo’s best scenario in the negotiations as getting the auto tariffs down to 10%, which would ease, but not eliminate, the pain.

Typically the cost of tariffs gets spread out — about one third falls on suppliers, another third on carmakers and a final third on consumers, according to Tatsuo Yoshida, senior auto analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence. He estimates a 10% tariff could be manageable over time, with gradual price increases of 2% to 3% a year and by updating car models to keep buyers interested. But as levies get higher, the strain becomes more acute.Tariffs close to 25% would likely leave at least a couple of Japan’s automakers on the ropes and in need of assistance, Yoshida said. “Like with General Motors during the global financial crisis, Japan’s carmakers are just too big to fail,” Yoshida said.

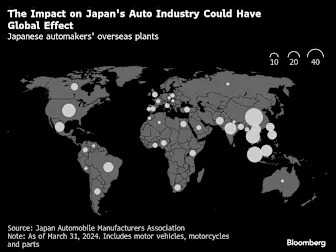

The numbers behind the auto industry show why all this matters. The sector employs 5.6 million people — or about 8.3% of Japan’s work force — and generates around 10% of gross domestic product, according to the Japan Automobile Manufacturers Association. It’s a pacesetter for wage trends in Japan, and plays an outsize role in trade. Automobiles and their parts account for a third of Japan’s exports to the US, the nation’s largest export market and the biggest contributor to Tokyo’s trade surplus with Washington — the very imbalance that Trump has long fixated on.

Out of the some 9 million vehicles built in Japan annually, 1.5 million are shipped to the US. Subaru is especially vulnerable, with 71% of its sales coming from there, according to Bloomberg Intelligence.

Subaru has said it will face a $2.5 billion hit from the tariffs in the fiscal year ending March 2026. One option is to shift some production to the US, where locally built cars are taxed less. But that creates problems for the many suppliers that depend on domestic manufacturing. Chief Executive Officer Atsushi Osaki signaled a shift may be necessary. Subaru “will continue developing our products in Japan, but it’s inevitable for us to expand our capacity in US,” he said last month.

Over at Daido Steel Co. in Aichi Prefecture, which makes magnets used in hybrid engines and employs about 12,000 workers, concern is rising. Although it doesn’t export directly to the US, the firm supplies Honda and indirectly all major automakers in Japan, so the impact of Trump’s tariffs will be significant.

“It comes down to how carmakers respond,” said Mikine Kishi, general manager of Daido Steel’s corporate planning department. “If they decide they’re not going to manufacture in Japan anymore, or that they’ll lower total production volumes, that would have an extremely big impact on our business.”

Some carmakers have already started to adjust. Honda has postponed its $11 billion EV supply chain expansion in Canada and is moving production of the hybrid Civic model from Japan to the US. Subaru is reviewing all of its investments, including the development of EVs. Nissan Motor Co. has halted US orders for SUVs built in Mexico, and Mazda is stopping exports to Canada of a model manufactured at its Alabama joint venture with Toyota.

Toyota, the world’s No. 1 automaker, hasn’t shifted production yet, but CEO Koji Sato said the company is consider building out its production footprint in the US in the medium to long term.

The calculation is different for small firms. For Hasegawa Yuuki Co., which employs about 50 people in Gunma, where it makes plastic parts for Honda, Subaru and Nissan, a 15% tariff is the dividing line between manageable and severe pain, according to President Noriyuki Hasegawa.

The company is already losing 5% of its business after Honda shifted its production to Alabama. “I don’t hold much hope for the talks,” Hasegawa said. “Japan doesn’t have much negotiating ammunition.”

Hasegawa is trying to shift focus to new sectors like furniture storage. “Our car-related business is certain to take a hit so I think we have to consider making products for things besides cars,” he said. “We’re going to need one or two other pillars to make up the loss.”

For others, the strategy is survival. At Ogami Co., another Gunma plastic parts maker for Subaru and others, President Hiroaki Ogami says he’s hitting the brakes on capital investment, while wage hikes next year look difficult. Larger firms may be able to weather the storm by expanding abroad, but smaller players like Ogami don’t have that kind of capital and manpower flexibility.

The company has a factory in the Philippines, but tariffs apply there, too. The charges could squeeze already thin profit margins of less than 10%, Ogami said.

Japan’s central bank is watching the situation closely. The Bank of Japan has long said stable growth and inflation depend on steady wage gains. Roughly speaking, that means wage gains of 3% to ensure price growth of 2%. For over a decade, the BOJ tried to engineer that outcome with massive stimulus, buying more government bonds and other assets than the size of the economy.

Core inflation has now held above 2% for about three years, allowing the BOJ to begin normalizing policy and start raising interest rates. But it remains cautious. Japan’s economy already shrank in the first quarter, partly because consumer spending is still weak, despite wages rising over 2%. Another contraction would tip the country into technical recession.

BOJ officials have made their concerns clear. In a summary of opinions at their April-May meeting, board members mentioned tariffs 27 times. One warned about the disruptions to supply chains, slower growth and negative impact on wages.

Just this week, Ishiba said his No. 1 pledge in next month’s upper house election would be to raise wages by at least 50% over the next 15 years. That implies annual wage growth of around 2.75%, a tall order if Trump’s tariffs stay in place.

Like many in the auto sector, Ogami said he’ll be watching tariff news closely, wondering if the new wave of protectionism will last beyond Trump’s term in office. His company has made it through the setbacks of the global financial crisis, the 2011 tsunami, earthquake and nuclear disaster and the pandemic, but he’s not so sure this time round.

“It’s not like we can just say, ‘Let’s just put up with it for four years,’” Ogami said. “If things continue like this, we won’t be able to survive. We need to come up with something.”

--With assistance from Yasufumi Saito and Shadab Nazmi.